“Learn the basics for mapping and documenting a wreck site by working with maritime archaeologists. Potential volunteer activities could include making archaeological drawings of the vessel, recording the site in photographs, and transferring the field drawings onto a site plan. If you are interested in volunteering, please contact…”

I saw the ad before the project, instead of in an old paper after the opportunity had passed. I was going to be here, not away at some event, or with family. Still, there were many reasons not to take this day off, such as responsibilities, deadlines, and rebuilding a house that is more demanding than any child could ever be. I ignored them all, and joined retirees, schoolteachers on their summer vacation, and Franklin Price, shipwreck archeologist, at a shipwreck here on Mount Desert Island.

“What ship?” “Why did it wreck?” “What was it carrying?” These are a few questions I have been asked when I tell people of my day deep in mud and covered with sunshine at the wreck site. And those are the very questions Franklin Price hopes to answer. The Seal Cove Shipwreck Project is an Institute of Maritime History project in conjunction with Acadia National Park. The ad said no experience required, but I could not imagine how a group of eager, untrained volunteers could be of much use, and not do any harm. Eager and untrained, I donned mud boots and sun hat, splashed on bug repellent and trotted off.

We gathered at the parking lot of the high school, and personalities began to announce themselves. A Florida resident spoke of getting his property boarded up for the winter, and how glad he was not to have to deal with snow. A teacher said she read we should bring muck boots, but preferred to wear her Tevas, and a young student arrived out of breath and apologetic. Her mom caught us just as we pulled out to hand over the left-at-home boots. The half hour drive to the site did not quite gel, the back seat could not hear the front, and so we chatted with neighbors or subsided and watched the scenery.

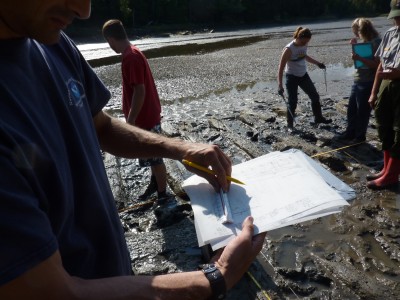

At the site other volunteers were already at work. The day was glorious. The dark ribs of the wreck were corduroy on the inlet bottom. Markers and tapes indicated areas where measurements were being recorded, and buckets above the tide zone were neatly filled with tape measures and slates–which to me looked very much like clipboards. The project was well thought-out and organized. We were given tasks in small understandable doses, and equipment, which we were shown how to use.

I was assigned a partner, a delightful young man who was not a random volunteer, but an archeology student. Lucky me. In addition to the very clear instructions from Franklin Price, this fellow explained why when we measure depth, we also run our hands under the beam. Our first task was to take a given beam from the hull of the boat, and measure where top and the bottom were in relation to a line we had made with two posts, a string, and a level. We took a measure every foot, and also drew in knotholes, wooden pegs, and on one beam, a stretch of tar. The tar was in a large pocket under the beam, and we recoded it going from 54 inches to 78 inches.

Our job was to collect data and record it. Greater minds can interpret. But, a patch of tar? We do not know, but speculate that a repair was made there. Other volunteers were also finding patches of tar. We asked Franklin about this, and while he would not commit to an explanation did say it was possible this ship had been brought in to the inlet for more repairs, and that the ship was beyond fixing, and so left there.

Unsure at first, the regularity of moving twelve inches and taking top measurements, bottom measurements and noting any distinguishing features became routine. Not in a tedious I-wish-I-was-someplace-else way, but in a I feel comfortable, I am gathering useful data, and I am in total bliss way. Any awkwardness on the ride over was dissolved as we shared bug spray, tips on moving around the site without falling into mud, and, oddly, finally exchanging names. We did not start as a team, then we paired off and so did not bond as a team, but as the morning wore on we shared delight over wooden pegs called treenails, which held the planking to the hull, tar, and worm marks.

Worms bore away at the wood of the ship’s hull, making a twisting pattern. While beautiful, the wood will eventually be eaten away. Not good if at sea. My archeological student partner explained that sacrificial planks were applied to hulls to decrease the risk of damage from worms. Attached to the outside of the hull, this half-inch thick layer of wood was replaced when infested with marine borers and discarded, or sacrificed, hence the name sacrificial plank. The fact that there were worm marks on our vessel indicated it had traveled in warmer waters than ours, since the worm making the mark lives in warm water, and does not survive long enough in brisk Maine water to make wormholes.

We also learned that the measurements we took of the ribs would help determine the original length of the ship. If the beams were ten inches by ten inches, the ship could not exceed a certain length. If they were twelve by twelve, it would indicate the ship was larger.

Hours disappeared into tiny notes on a slate, and then the tide turned. The very shallow basin of this cove means the tide comes in fast. Absorbed in our hull ribs, we did not want to pick up until we finished our measurements, and the drawings that went with them. Tide was pushing us, and we reached out and helped each other, exchanging tape measures, helping record, doing whatever needed to be done to make sure each pair had their data and measurements done. No competition, no discussion, we just did it. Franklin moved from group to group, running confirming spot checks, and helping us finish up. I felt like a proud kindergartner when he picked up my slate and double-checked three random measurements. All were within acceptable range. I glowed. We all did. A mark of a good leader is making everyone feel valued, and we all felt that.

We stood ankle deep in water, the wreck totally submerged. It was satisfying as we gathered our tools, tape measures, levels, and our hand drawn charts. We came away knowing what it is like to do archeological research. We learned trilateration, baseline offsets, drew profiles, and measured and measured and measured again. We understood the importance of accuracy, and double-checking numbers that may be gone in a few years, and beyond being checked. We learned to look with our fingertips, as they moved gently along the bottom edge of a hull rib, out of sight under the water. We know what a sacrificial plank is. I went to learn about history and archeological process, and I did, but I also came away with a renewed appreciation of diligence, painstaking accuracy, and working slowly, carefully, and methodically. The tide was coming, but we did not rush or make hasty calculations. Standing in the sun, with sleeves rolled up, giving and getting help, we were united, calm and competent. It was a day outside of time.