What do you mow, or perhaps smoke, and is always greener in the neighbor’s yard? It is grass, of course, a part of our everyday lives. It is so much a part that we often do not even think about it. If it is summer and you are outside, chances are you can see some grass right now. Close your eyes, and instead of lawnmowers and recreational drugs, conjure images of delicate bouquets, or even origami. That is grass, too.

As spring turns into summer with colorful petals in fuschia, purple, and yellow, my love of tree flowers blooms into grass flower love. I hear that grass ID is not really hard, it just involves different nomenclature. I do want to believe this, but I have yet to crack the language barrier. Until then, I peer at shimmering silver grass stigmas through my hand lens and sigh in awe. I glance at the glossary in my manual of Northeast grasses. Foveolate (covered with small pits) and glume, (one of usually two empty bracts at the base of a grass spikelet) remind me that they are just words. If I could get through Middle Welsh in college, surely I can handle a few more plant words.

Instead, I close the book and wander down the hill behind my house into a meadow with an assortment of grasses. I pass the other graminids, sedges and rushes, by the stream, but they can wait for another day. I gather dock, ninebark, multiflora rose and a handful of grasses. As with many bouquets I pick roadside, care will be taken to prevent moving seeds from the many invasives that line my street. I select one grass I have tentatively identified as Dactylis glomerata, commonly called orchard grass, cat grass, or cock’s foot grass. I place it in the upper edges of the large, and in my opinion stunning, centerpiece. Who would want a hothouse arrangement of hybrid roses when all this glory is waiting right outside the door? Plus, as I eat, I get to practice the scientific names of my bouquet stems.

A few days after picking my bouquet, I ordered chai at a take-out coffee shop. A row of small ceramic vases showed they, too, used roadside blooms. Poking out at the top was a frothy spray of panic grass. The owners and I shared a moment of grass worship. Grass flowers may be under-appreciated, but they have admirers in unexpected places.

Grasses also have many dependents, including humans. We eat bread made with wheat, live in shelters made from bamboo, and breathe oxygen produced from green blades of grass. Another creature depends on grass, too, for shelter and life. This is the creator of the neatly folded grass blade pictured above, the sac spider.

In June I start looking for these twice or thrice-folded blades, greeting them anew each year. In 2020, I had the opportunity to watch a female spider as it worked on sealing itself up. I also took a photo of it, and was able to give it a name. It is from the genus clubiana. These spiders seem to favor the flat blades of bunch grass. I am thinking this may be Phalaris arundinacea, Reed canary grass. The spider folds it gently so the vascular bundles continue to function, keeping the grass alive. I’ll bet there is some very cool word for these bundles, but I don’t know it yet. The spider then sends silk from her spinnerets, pulling the folded edges of the grass tightly together. As the silk dries it shrinks and stiffens, and the nest is complete. In the safety of this shelter, she lays her eggs, generally 17 to 112 according to Wikepedia, and she stays with them until their first molt. Some sources say she is their first meal which would be true mother love. If so, it is an example of matriphagy, which some sac spiders do practice, but this is not clear.

This year there are many more origami nests than in previous years. I counted over one hundred and fifty from one spot, and sometimes there were multiple folds on a single stalk of grass.

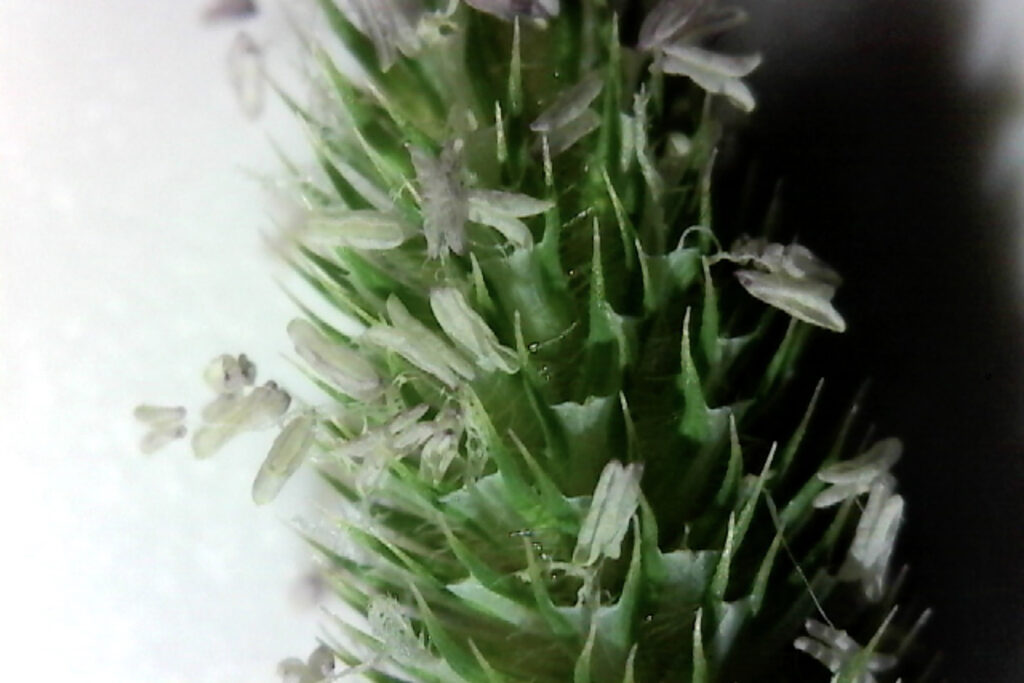

I am at the beginning of my grass learning adventure, and not sure how far I am going to go. I have taken a few walks with some amazingly knowledgeable botanists. My toes are getting wet. Timothy grass, Phleum pratense, is the only grass that resembles a miniature cattail, making it super easy to ID, and is one of the first grasses I learned. It was introduced from Europe by Timothy Hanson, an American farmer. Why it wasn’t called Hansen grass I do not know. If you want to go down the grass path too, here are some excellent places to start:

Agnes Chase’s First Book of Grasses: The Structure of Grasses Explained for Beginners

Grasses and Rushes of Maine, Matt Arsenault, Eric Doucetter, Glen H Mittelhauser

Grasses of the Northern Forest, Jerry Jenkns and Brett Engstrom

Grasses, Sedges, Rushes: An Identification Guide, Lauren Brown and Ted Elliman

Happy grassing, and I hope to see you on a grassy path.