I was never a slug fan, and I know I am not alone. My nephew and I once bounced ideas for a book called 101 Uses for a Slug, and most of them involved the slug’s demise. They munch garden plants and leave sticky slime trails on the window screens. People who are lazy are called slugs. What is there to love? Turns out, there is more than you might think.

Terrestrial gastropods without shells are commonly called slugs, and that is because these gentle, slow-moving creatures reminded someone of slow, lazy people. Plodding humans were not called slugs after these shell-less mollusks, it was the other way around. It wasn’t until the 1700s that the word slug was used for this creature. I am not sure what they were commonly called before that, but it probably wasn’t a terrestrial gastropod without a shell.

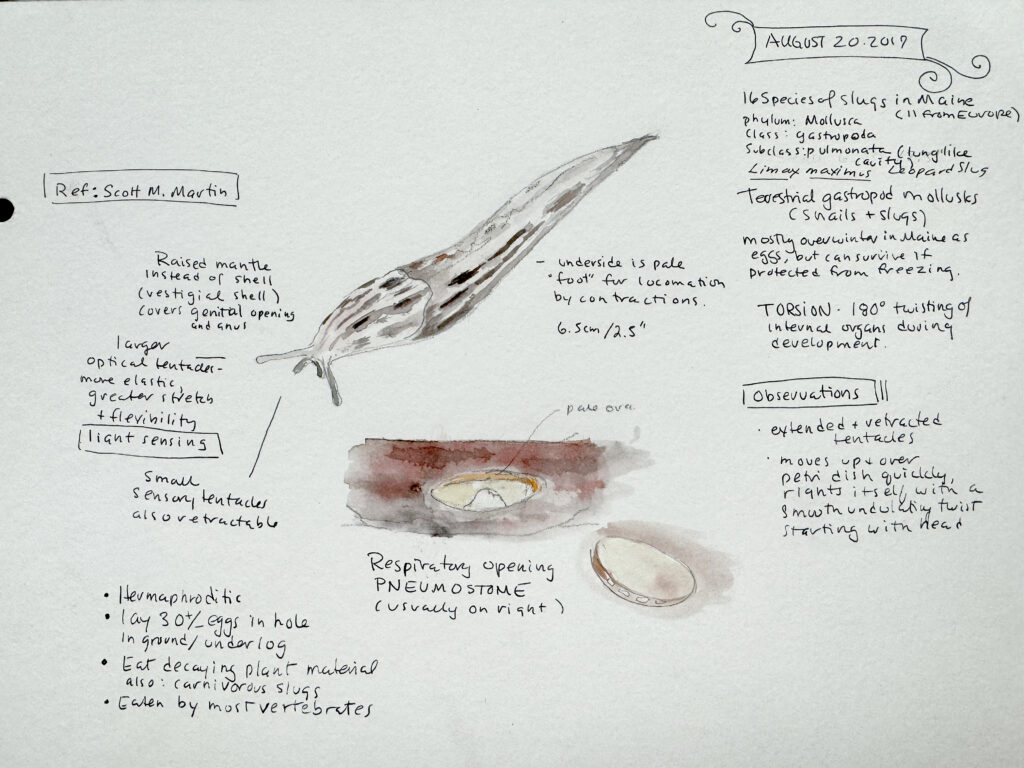

I had my slug epiphany one morning when I awoke in my summer bedroom, a screened sleeping box about 100 feet from the house. A four-inch leopard slug, Limax maximus, was gliding up the outside of the screen. Perhaps I had been having warm, sweet dreams, or was just so snuggled and content in my comforter that nothing could cause dismay, but instead of getting up to flick it off, I watched bemused as the pale foot contracted and stretched and the slug climbed higher. I finally tossed off the blankets and set it on the palm of my hand for a closer look.

I could see it breathing.

I held my breath and watched. A small oblong opening was very slowly opening and closing. It was the pneumostome, which is what a slug uses to breathe.

Leopard slug breathing from Karen Olga Zimmermann on Vimeo.

Years of slug unappreciation flipped in a second. I even forgave them for an early slug trauma: I once ran barefoot across a brick walkway, foot slamming down on a slug foolish enough to be in the line of traffic. The force ruptured the slug, whose parts flowed up between my big toe and its neighbor. For those of you who may not have experienced this, slug flesh is not easy to remove. I spent some time on the edge of the tub, scrubbing between my toes with a pumice stone. It took days before it was gone.

I became enamored of my new slug friend, observed it closely, nose to tentacle, and sketched it in watercolor. We were firmly bonded, without the need for slug bits between the toes.

I looked for more information about my slug and found a few resources online. This slug is introduced, as are 11 of Maine’s 16 slug species. Of the native slugs, four are from the family Philomycidae, and one from the family Limacidae. Some people have life lists of birds, I now have a life list of slugs.

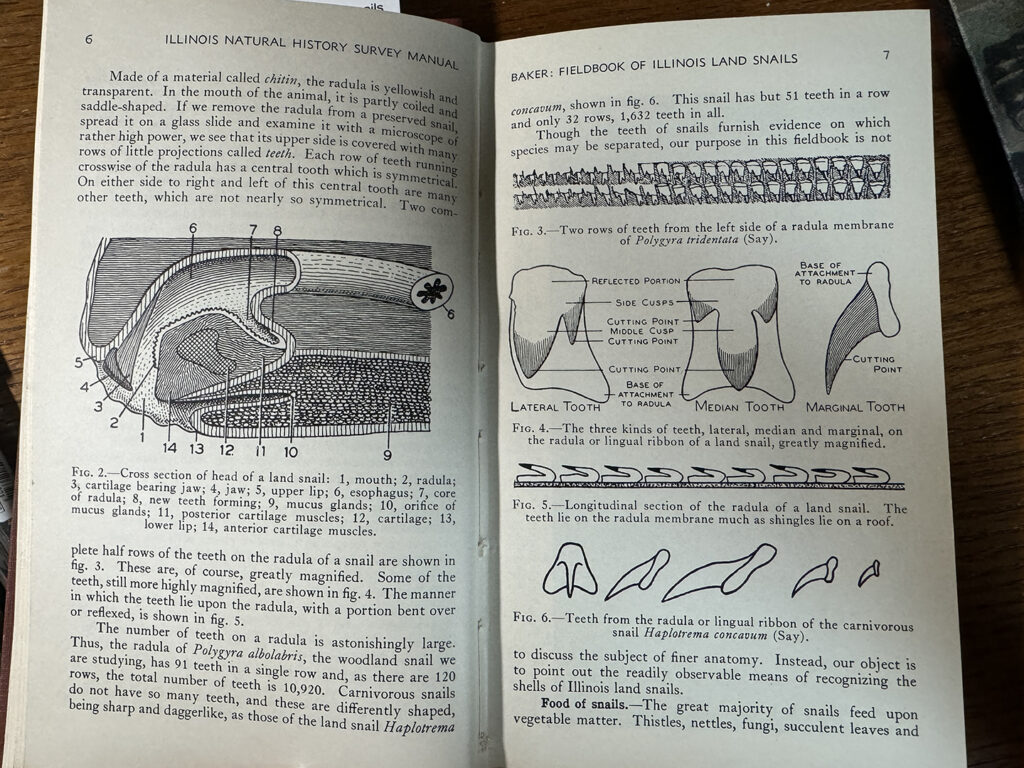

My slug interest had been on simmer but is slowly heating up. Last summer at Riverow Bookshop, a favorite second-hand bookstore in Owego, New York, a slim maroon hardcover titled Fieldbook of Illinois Land Snails, by Frank Collins Baker, jumped into my tote and came home with me. Published in 1939 the illustrations by Dr. Carl O. Mohr of a land snail’s head, cross-section of a radula, and many species of terrestrial gastropods clearly show slug anatomy and field characters.

At a recent book auction at the Josselyn Botanical Society summer meeting there was a kraft paper bag with “SLUGS!” neatly lettered on the front. It was bulging with copies of articles on slugs, and included Terrestrial Snails and Slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Maine, Northeastern Naturalist by Scott M. Martin. Add to that a key to the Land Mollusks of Northeastern United States and Southeastern Canada, Getz, Chichester, and Burch, and I was armed to go forth and Identify.

I have with tentative confidence seen Arion ater, the Black slug, Arion subfuscus, Dusky arion, Limax flavus, tawny garden slug, and the one we all know and love or hate, Limax maximus, the leopard, or spotted slug. Like the expanding of a Limax as it moves across a surface, my feet have expanded along with my years, and are now a solid size 6.5. That is about 8 inches. Limax have more than once stretched longer than my foot. It well deserves the name “maximus.”

Naming slugs may be a challenge, but enjoying them is not. A slug pushes itself across a surface in a remarkable form of locomotion, excreting a slimy mucus over which it glides. As it contracts and expands, the dark spots on a leopard slug’s back create a series of patterns, as enthralling as any kaleidoscope. Thanks to Mohr’s snail’s head illustration, I know where all the glands producing copious amounts of mucus are located. I can watch as the pneumostome opens and closes, and tentacles searching for obstacles as the slug moves forward.

I seem to have missed the ballet as two slugs mated outside my door. I saw them moving in harmony across the step, one following the other with little nibbles, but they moved under the floor, where I could not see them. Perhaps they hung suspended together there for a brief moment of slimy love. If you have not watched their entwining and sharing, this mesmerizing mating has been captured by David Attenborough and the BBC team.

Slugs can induce shudders of disgust, but fireflies lure people out to gaze in wonder at their flashing lights. There are even ecotours in North Carolina to watch the annual courtship of synchronous fireflies, sold out well in advance. I am not sure anyone has started an ecotourism business to watch our gliding mollusks. In the case of firefly vs slug, the firefly wins. They not only have a huge fan following, but their larvae are voracious, aggressive predators of slugs. If you want a field of glowing lightning bugs, you’ll have to tolerate a few slugs.

Fireflies suck up the soft body of slugs, after liquifying it, but slugs are not entirely soft. Their radula, a ribbon-like rasp, is used for eating. It is their only hard part and is made of chiton. The radula has rows of sharp protrusions, commonly called teeth. These teeth get worn out and replaced throughout the life of the gastropod. How many are there? It varies with species, but some may have as many as 27,000 at any one time. As slugs move over the top of a mushroom, they rasp away at the surface, sanding off food particles that get passed into their gullet. Crouch down over the next slug-chewed fungus you come across, and you can see the minute trails and rasp marks left behind.

Slugs, named after slow plodding humans, are far more interesting than their namesakes. Undulating, gently breathing, and sporting 27,000 teeth, they are worth taking a closer look, eye to stalked eye.

More about terrestrial gastropods

Land Mollusks of Northeastern United States and Southeastern Canada, Lowell L. Getz1, Lyle F. Chichester2, and John B. Burch3

Scott M. Martin, Terrestrial Snails and Slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Maine. Northeastern Naturalist