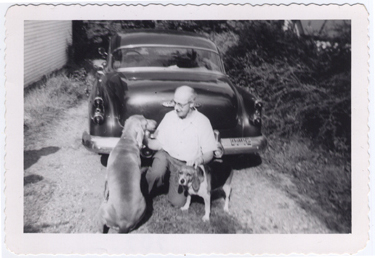

Hughie Wright with Freckles (the beagle) and Missy (the Weimaraner)

in Seal Harbor, Maine courtesy Jackie Davidson

Hughie Wright was a Seal Harborite, fly fisherman, loyal husband, maker of whiskers and Edsel and Eleanor Ford’s houseman.

One does not hear the word houseman very much any more. There are caretakers and estate managers, but houseman is rarely used. Yet it was a respected profession only a generation ago. A houseman was a trusted and essential employee. Most of the families that summered in the neighboring villages of Seal Harbor and Northeast Harbor would have a houseman. Hughie Wright was one of the best.

There is no trade school or correspondence course for houseman. It was a profession frequently passed on from father to son, and always learned on the spot. Hughie was self-taught. His job was, quite simply, to ensure the family he cared for had a perfect stay. He molded his skills to the desires of his employers Edsel and Eleanor Clay Ford during their stay at their summer home, Skylands. This was not demeaning, but rather a matter of pride. It takes keen observation, real affection, and a wide range of skills to be a good houseman. The bond between Hughie and the Fords, who he referred to as his “family” was the best of a master and servant relationship. Together over fifty years, Hughie called Eleanor Mother Ford and was devoted to her, even bringing her shoes home to clean at night. The Fords in turn depended on him, and took care of him.

At Skylands, cool Maine evenings were commonly warmed with a birch fire. Birch burns with snaps and cheery crackles, looks clean and pristine, gives off a lot of heat, and is the wood of choice for open fireplaces. One of Hughie’s many responsibilities was the building of the fire. And so the whiskers.

Whether it was Hughie’s grandfather or the Ford children who coined the phrase whiskers is uncertain, but old-timers still talk about Hughie’s whiskers. They are referring to his fire-starters. Every winter he would take clear pine, a beveled jack knife and make whiskers. He would spend close to half an hour on each one, shaving eighteen-inch lengths of pine board into thin curls. He then put them in a vise and used a drawshave to smooth their spine and drilled a hole hang them for storage.

Whisker, or pine fire starter c. 1960. Hand-shaved by Hughie Wright

Hughie learned to make the whiskers from his grandfather, starting when he was five years old. By the time he was a teen, he was allowed to make the whiskers not just for the kitchen fires, but for the living room as well. When Hughie started work at the Ford home in 1926, he introduced the fire starters and they at once became a required element in laying a fire. There were nine fireplaces in the house, and it took all winter to create a supply for the following summer. When stainless steel pocketknives became the only kind readily available, Hughie had a blacksmith hand-forge a beveled edge knife for him, so he could continue to shave the thin curls of the whiskers. Wood became more difficult to find too, but Hughie sought out clear pine, as pink was not acceptable in the Ford house.

There are only a few of these whiskers left. We were given one by Jane Smith, my mother-in-law, who is not sure how she ended up with it, and there is one in the Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. When Margaret, Hughie’s wife, died, she believed there may have been a few still left in the whisker closet of Skylands, now owned by Martha Stewart.

Skylands, where Hughie Wright was Houseman

Hughie lived the life he wanted, and being remembered for his whiskers would please him. They epitomize his quiet quest to make life good for his family. He was never one for glory, but was well mannered, professional and dignified. Married over forty years to Margaret, he went to work every day. A familiar sight in Seal Harbor with his long-billed hat and cigar in hand, he was a man of routine. He went home for lunch every day, and Margaret would make a large and hearty meal. Every evening he would shave a few whiskers. Every year he and Margaret went to the annual Wayback Ball, a social gathering held after the departure of all the summer folk. He fished in the spring, raised Springer Spaniels, and in the winters sometimes had a nip or two with friends. Not given to jokes, a rare example of his humor is the sign for their dog kennels, designed to emulate the signs of the wealthy cottagers. Small and discrete, it reads Dogterd Ridge.

Sign from Hughie and Margaret’s Kennel in Seal Harbor, Maine

Collecting the mail was part of Hughie’s routine, and all summer long without variation he would stop at the post office after lunch.

On one of those summer days, no different from any other, he dropped dead outside the post office. Margaret had made her fried clams, each individually dipped in batter and tenderly browned, and sent him back to work. Jackie Davidson, a family friend, says “Margaret said it was a terrible shock, but that Hughie would have hated being sick, he’d have made a terrible patient.”

The art of shaving whiskers is gone, too. Hughie tried to show others how to carve them, including directions for the hand-forged knife, but was never able to pass it on. We will keep ours in a safe place.

Thank you to Jackie Davidson, Rodney Smith, Jane Smith, and David and Muriel Billings and for sharing their recollections and photos of Hughie.

Dramatis Personae is a series of portraits of Otter Creekers, and other local characters.